A Maltese court, presided over by Mr. Justice Toni Abela, recently ruled that journalists, in their role as public watchdogs, must have access to detention centres in which migrants and asylum-seekers are held and to Corradino Correctional Facility [Emanuel Delia Vs L-Onorevoli Byron Camilleri et. Rikors Numru 201/20TA, December 2023]. In a case instituted by Maltese journalist Manuel Delia, it was argued that the refusal to allow access to journalists to detention and prison is a breach of the right to freedom of expression and allows for the actions of the authorities to be subject to public scrutiny.

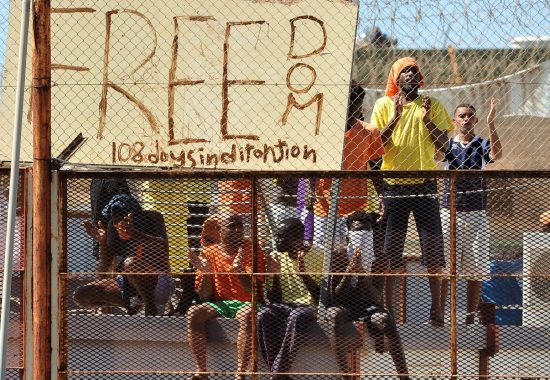

The recognition by the Courts of the public interest value in the reporting from and monitoring of certain locations where vulnerable groups are being held is of paramount importance. Access to migrant detention centres by civil society has always been tightly regulated and, more recently, outrightly prohibited. Lawyers working with non-governmental organisations have also been effected by more restrictive visiting policies in recent years. Such policies include severe restrictions on visiting hours, number of clients to visit, indication of police numbers of recently disembarked asylum-seekers and a restriction on the use of IT equipment.

The lack of proper access by journalists, NGOs providing services and lawyers results in the Government having absolute monopoly over the type of information, if at all, which is available to the public. As a consequence of this, as pointed out by the Court in this landmark judgement, the public is denied objective and balanced information on the conditions and treatment of detained migrants and people being held in prisons.

Content of Access

The Court found the policy, that journalists had to adhere to when visiting prisons, to be so restrictive as to be described as “suffocating” and “ominous“. Such policies dictated how interviews may be carried out and what behaviour and equipment is prohibited. The policies also stated that the visit route would be decided by the authorities and that the visit can be terminated at any point by the authorities. Although the Court recognsied that there is a need for rules, it noted that such rules should not have the effect that journalists had their hands tied and could not effectively carry out the reporting they set out to do.

Significantly, the Court held that the right to freedom of expression doesn’t only cover the content of such expression but also the method in which such content is recorded or collected. It held that journalists should be allowed to take photographs, record interviews with microphones and also take videos, always whilst respecting detainees and prisoners right to privacy.

“L-Awtoritajiet ma għandhomx jagħlqu l-bieb tagħhom lill-ġurnalisti, għaliex dan ikompli jnissel u jsaħħaħ dubju u ħsiebijiet li hemm tassew għalfejn wieħed għandu jinvestiga”.

(Informal translation: The Authorities should not close their doors to journalists, as this increases and strengthens doubts and suspicions that there exists a real reason to investigate)

The Court held that the denial of effective access creates a chilling effect on the carrying out of independent investigations and reporting of incidents in places of detention which the government would prefer to never come to light.

Significant Relevance to our work

The monitoring and holding government to account for the treatment of persons deprived of liberty is crucial in view of a host of Strasbourg judgments finding Malta guilty of inhuman and degrading treatment in their detaining of migrants. These judgments include A.D. v. Malta decided in 2023, Feilazoo v. Malta decided in 2021, Abdullahi Elmi & Aweys Abubakar v. Malta decided in 2017, Abdi Mahamud v. Malta in 2016 and Suso v. Malta and Aden Ahmed v. Malta decided in 2013. It is crucial that civil society, including journalists, are allowed to access and report on the conditions endured behind the closed security gates of migrant detention centres and Corradino prison.

We recall, for example, the death in detention of Nebil Abdula who died after falling from a height at Lyster Detention Centre, and the death Mamadou Kamara and Ifeanyi Nwokoye who both died after being beaten by detention and AFM officers whilst in their custody. We cannot forgot the shooting of migrants by unlicenced private security guards at Safi Detention Centre in 2020, the use of rubber bullets in 2011 and the reported use of excessive force during protests also in Safi in 2008 and 2005. Not to mention the scores of migrants and asylum-seekers found by the Maltese and Strasbourg courts to have been detained illegally over the years.

Such events as the ones above only come to light through the work of NGOs in detention, journalists reporting incidents in newspapers and cases filed lawyers on behalf of clients brave enough to challenge the system. We can only imagine what additional information would have available had journalists managed to speak to witnesses and victims of these incidents. We can only imagine what other incidents never saw the light of day.

Hope for change

We hope that this judgement results in increased effective access, not only for journalists, but also for lawyers and NGOs that provide a service to persons who are deprived of liberty. Such access needs to be effective and not overly suffocating. Journalists, lawyers and NGO need to have their mind at rest that they would be allowed to carry out their work in the best possible manner with the use of the tools of their trade, such as cameras, IT equipment and laptops.

Access to such places serves a multitude of purposes, including the betterment of conditions for those individuals being detained, a reduction on the strain put on detention services, transparency of procedures and ultimately accountability of Government towards human rights standards in the country.

This post was written by Carla Camilleri, with the ambit of the Strengthening Access to Justice for Improved Human Rights Protection project funded by the