Reform Process

Throughout this year we will be looking at Venice Commission Opinion CDL-AD(2020)019 adopted in October 2020 on the acts and bills that sought to implement the proposals for legislative changes which were the subject of Opinion CDL-AD(2020)006 adopted in June 2020. In this post we examine the Venice Commission’s reaction to the procedure used by the Government in adopting the first 6 Acts which are subject of the Opinion.

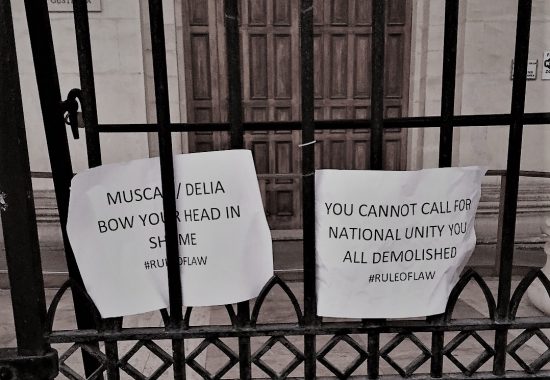

Backdrop: Daphne Caruana Galizia’s assassination

On the 8th October 2020 the Venice Commission adopted an Opinion on the ten acts and bills implementing the legislative proposals put forward by the Maltese government. This is the 4th Opinion adopted by the Commission on Malta since 2018. The process relating to the Malta’s constitutional amendments, separation of powers and independence of the judiciary kicked off in October 2018 by a request of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) to the Venice Commission.

The request to the Venice Commission from the PACE originated in a proposal by the Rapporteur of the report on “Daphne Caruana Galizia’s assassination and the rule of law, in Malta and beyond: ensuring that the whole truth emerges”. The Venice Commission had noted then that the request for should be understood against this backdrop, although its remit is exclusively limited to the examination of Malta’s constitutional amendments.

Reaction: A hidden & rushed parliamentary process

Interestingly, it can be noted that the Government transmitted the 10 bills to the Venice Commission as restricted documents which could not be circulated to the public without prior authorisation. The Minister requested an opinion by way of urgency, to which the Venice Commission replied by stating that it would not prepare an opinion by way of urgency but that it would be finalised at the beginning of October 2020.

The Venice Commission also recalled that it had insisted that the Maltese authorities should have a meaningful exchange with all stakeholders on the basis of texts that should be public. It strongly called:

“… for wide consultations and a structured dialogue with civil society, parliamentary parties, academia, the media and other institutions, in order to open a free and unhampered debate of the current and future reforms, including for constitutional revision, to make them holistic. The process of the reforms should be transparent and open to public scrutiny not least through the media.” – paragraph 99 Opinion CDL-AD(2020)006.

The lack of publicity of the texts up until the last minute meant that bills, that will have profound and long-term impact on Maltese society, were not scruntised by civil society, parliamentary parties, academia, the media and other institutions. This was done against the repeated recommendations of the Venice Commission that called for wide consultations with society as a whole.

Cutting short any meaningful dialogue

In spite of this, on the 29th July 2020, the Maltese Parliament went ahead and approved 6 out of the 10 Bills it had previously presented to the Venice Commission. In reaction to this, the Opinion noted with regret that the Bills were adopted before the Opinion could be finalised and without any structured dialogue with all stakeholders as recommended.

The Venice Commission stressed that it was “critical of the procedure followed by the Maltese Government, which it regrets” and that the rushed and opaque procedures essentially cut short any meaning dialogue with Maltese society. It noted that the 6 wide-ranging bills were rushed through Parliament in just 29 days between the first reading and adoption. Furthermore, it noted that 4 bills were made public after 16 days from their presentation at first reading in Parliament.

Unanimity in the Maltese Parliament is an ambivalent matter

In scathing words, the Venice Commission noted that confining discourse to the political parties in parliament, without meaningful public consultation, was akin to denying citizens their democratic entitlement to have a say in the shaping of the constitutional order of Malta. The text of the Opinion goes so far as to say that although unanimity may be seen as a sign of broad consensus, it could also be interpreted as:

“proving the closedness of the political system and the fact that common vested interests bind the majority and the opposition together.” paragraph 16 – Opinion CDL-AD(2020)019

Finally, the Venice Commission repeatedly states that the procedures adopted by the Maltese authorities in carrying out these reforms go against the literal and overall thrust of their previous opinions.

In a furture article we will look at the substantive comments to 6 acts adopted by Parliament relating to:

- Reforms relating to the judicial review of decisions not to prosecute;

- Amendments to laws regulating the Office of the Ombudsman;

- Constitutional amendments relating to the appointment of the judiciary;

- Constitutional amendments relating to the appointment of the President;

- Constitutional and other amendments relating to the removal from office of the judiciary; and

- Reforms relating to the appointments to the Permanent Commission Against Corruption.

In May 2020, aditus had the opportunity to discuss its views on the proposed changes, together with other local civil society actors, with the rapporteurs of the Venice Commission. This was followed by a publication of its feedback on Malta’s proposed legislative changes. We had already then noted our frustration at the lack of broad civil society involvement in the formulating any of the intended changes put forward by the Government.